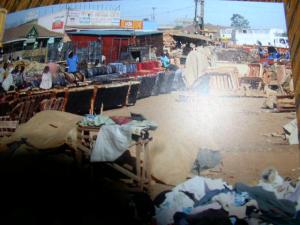

The center of Kitale is like being in a traffic jam, although there are no cars and nothing is stalled, everything is fluid, everyone is in motion – people, cows, sheep, cops, street vendors holding up pink beads, cords, radio’s, scarves, key rings, old candy, mirrors. Motorbikes and Manitoo’s stop on a dime, offering no signal, just picking up a passenger where ever they are standing as long as they can cram one more person in the already crowded bus. The Manatoo’s speed seems amazing given that they look as if they are so full of passengers, luggage, boxes, tied to the top that they may tip over at any moment, yet they cross four corner intersections without traffic signs or stop-lights and I stare in awe, wondering if I’ll ever be able to cross the road and what are they trying to construct by dumping a pile of dirt in the middle of a dirt path or if the boy trying to cross the intersection will stay alive.

This is the contemporary, complicated area of Kitale, a small village with the hustle of a big city, it’s go-go atmosphere doesn’t have the poshness of a New York, but it out does New York by its mix of wild-life searching for street space and its never ending winding streets that are more like dirt paths. They stretch out like a river breaking free of its determined course and run every which way, without street signs to guide you. My heart speeds up at the thought I will never be able to retrace my steps and get back home, for my little cottage feels like home to me now. I put an African violet on the small table I use as a desk and tie the curtains back with some shipping plastic someone had left.

I walk past a museum that has a statue outside and decide to go in. The fee is $10,000 shillings ($10.00) for non-residents and for that money I’m given a guide who is telling me of the early life of villagers and it looks to me that the stuff in the museum still represents the life of the village today. It doesn’t appear to be something that happened long ago and doesn’t happen anymore. People in the countryside still live in the same mud huts with monkey’s screeching in the trees and children running barefoot in the heat of an afternoon and men with many wives and women doing most of the work and sons treated as kings and many daughters continue to be circumcised.

I’m intrigued by a sculpture garden, statues of Jesus and Moses on the mountain top. A nature walk through a forest is alive with monkeys, both black and white hiding in trees. We cross a wooden bridge made out of tree branches, and the swamp water is golden, reflecting the mossy tangle of roots, spreading out like ancient ruins. The air is filled with smoke from women cooking over their wood fires. After crossing another bridge, we are out of the forest and came to an open field of mud and grasses. My guide tells me it is a sanctuary for all animals that were born deformed and would have died or have been killed because they were of no use to anyone. With pride, he points to a one legged goat, a four eyes cow, two lambs attached to one another. He carefully points to each deformity and tells about it as if it was a prized gift from God, not something to pity and I think the animals are luckier than many people.

Jill

/ May 21, 201410,000 shillings= $10! I would be spending all day trying to figure out the money!

Betty LaSorella

/ May 21, 2014It did seem like I was spending a fortune at times..

Rose Minar

/ May 21, 2014Sis: This essay is exquisite. I saw you there, in color—and joined you on your fascinating day.